A beginner's guide to accounting fraud (and how to get away with it): Part IV

Buy now, pay later

Previously, on A beginners guide to accounting fraud, we:

§ Bought a fruit distribution business that never made any money, for not very much (because companies that don’t ever turn a profit aren’t really worth anything);

§ Had a friend set up shell corporations for our new business to bill, adding a little bit to revenue but a whole lot to profit (because sales that aren’t real don’t come with any costs);

§ Announced plans to develop a software product for managing fruit logistics (so investors started looking over here);

§ Span off some of the old distribution ops to “management”, along with all the uncollected receivables from fake sales (while no one was looking over there);

§ Raised a shed load of new equity from private investors at a multiple of very forward looking sales, based on the total addressable market for fruitware

So far so good. If we just sold our stock in the company we’d make out ok. But I’ve got a taste for this now, so we aren’t going to settle up our tab just yet are we?

We can’t stop with the fraud either. Sooner or later some sell side analyst is going to get round to doing actual work of their own, like a monkey with a laptop. They might even point out the obvious fact that we still really aren’t producing any cash for our owners. We’ve bought ourselves time before that reckoning happens, by shuffling receivables and promising a new product. Now what? Now we buy something for real, so that it never does.

Just not with the actual cash we got from new shareholders. We don’t want to be giving that away.

And not something that has any substance either. We’re not trying to build a sustainable business here, are we?

Let me try and explain how this could work, by way of an example. I am, of course and as usual, not suggesting at all that there is anything wrong with this particular transaction. Just that, like before, we could do something similar if we want to make it look like we are paying good money for real assets (when in fact we are paying very little for even less). This one comes from a thesis I went through with an activist short seller in the US, the often cryptic Dan Yu (better known as the founder of Gotham City Research). Last I heard he’s now involved at General Industrial Partners with Cyrus de Weck, and Gotham is out of hibernation:

We’ll begin with a small deal, like I did with Dan when I started explaining it to him, to make the mechanics really obvious:

In September 2011 Quindell (at the time trading as Quindell Portfolio PLC) acquired a business called Quindell Solutions Limited (QSL).

QSL had previously been a subsidiary of Quindell Limited, which in turn reverse merged into Mission Capital in May 2011, to form the then listed business called Quindell. All clear?

In 2009 Quindell sold QSL to its CEO Rob Terry in for a pound. Companies House filings show it had a slightly negative book value at the end of 2009 and again in 2010; sales, costs and cashflow were all nil. So QSL was an empty shell.

In 2011 Quindell re-acquired QSL for two hundred and fifty grand in cash (£251,000 to be precise). At the time it was wholly owned by Quob Park Limited, which was in turn wholly owned by Rob Terry. Quob Park’s previous name was Quindell Portfolio Limited.

If you’re still following, Rob and his wife Louise Terry were both Directors of Quindell (the PLC) and of QLS / Quob Park when the acquisition took place. But it wasn’t disclosed as a related party transaction. I mean this was AIM after all.

So it looks a lot like Quindell made a large undisclosed payment to its CEO, for an empty shell company that it had sold to the same CEO two and a half years earlier - for a pound. Perhaps, surely, there was some great innovation at QSL in the mean time that justified the cost. But there didn’t have to be. And in our case there won’t be.

I should mention that Quindell sued Gotham for libel, and won. Now that could have something to do with the fact that Dan, who was based in the States, didn’t bother to show up in court. Some might even say it was “a worthless and unenforceable judgment”. But I don’t want to be making a trip to the High Court either, so I’m sticking to only recounting the basic facts here. If you want a better feel for what Quindell was really about you might try checking in on Australian law firm Slater and Gordon. It acquired what it thought were Quindell’s good assets after the share price tanked in the wake of Gotham’s report. And, to be fair and balanced, if I remember right Gary Lineker did do very nicely out of its Ingenie business.

That’s enough on that, let’s talk more about us. Now you might think the way to go is having our old friend set up a few more shells – we could call them Himex and LearnEd and Quindell Enterprise Solutions and so on. Every few months we announce an exciting acquisition to our retail shareholders, the ones we raised all that capital from last time out. We’ll say we are buying in key tech for our Lemonware product (adding lots of AI functionality, naturally). But all we would really be doing is paying out those readies to ourselves. We could get comfortably rich looting the company.

End of guide, right?

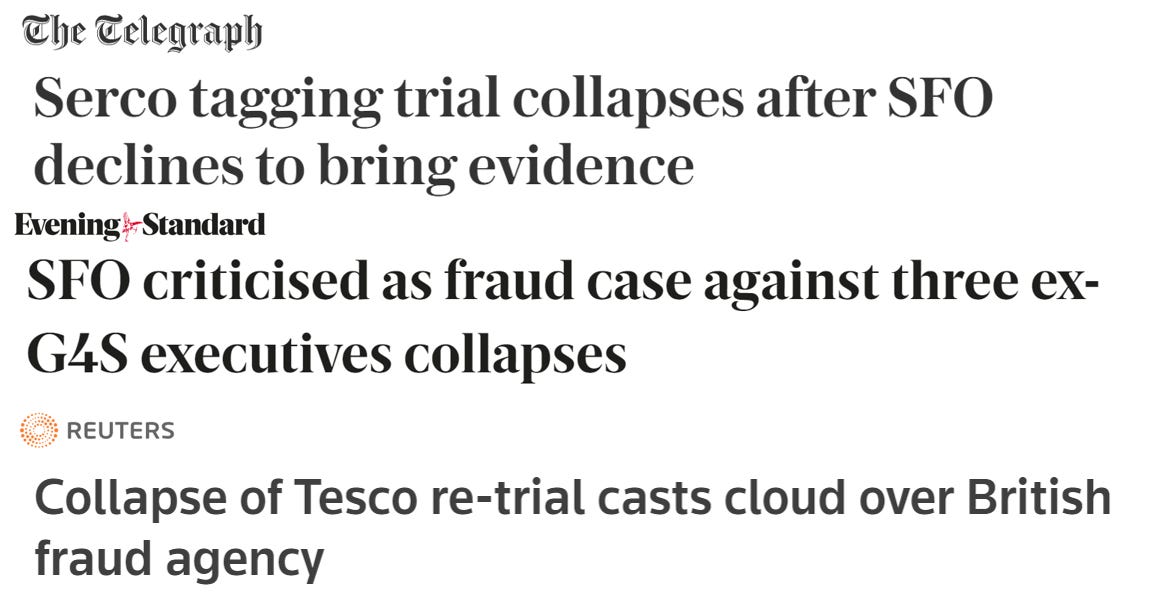

We could, but I don’t like porridge that much. And stealing money this way leaves a trail so obvious that even the Serious Fraud Office might be able to follow:

Anyway, I want to wring a couple more instalments out of this before we’re done. So here’s what we are going to do instead…

When we buy something it won’t be about real money changing hands. Both sides of our purchases will be as made up as our products. Well, almost. It’s a bit too blatant to say we paid hundreds of millions for a company that is obviously just a shell. We at least need something that’s had a working webpage for a few years. So we don’t quite buy nothing. We buy a small business, for maybe 10 times what it is worth (so the owner is very happy). But then we book it in the accounts at a cost that’s 10 times that again (so it looks as though that’s where our cash is going). Like when Wirecard claimed it paid over €300m for parts of the small travel ticketing business, Great Indian (GI) Retail Group (the main subsidiary acquired was Hermes I Tickets):

Never mind that GI’s own accounts, and foreign direct investment data from an Indian government website (credit to Eduardo Marques, now of Pertento Partners, for digging this up), both showed that the amount paid was more like €30m:

A quick note to self. You probably spotted that the investor listed here isn’t Wirecard, it’s some blandly named Mauritius entity. Now that we are upping our game this is the kind of detail we need to take care of too. We want to to run our deals through offshore jurisdictions that block outsiders from seeing what is going on or who’s really behind the scene. We could probably use Cayman or the British Virgin Islands, the Netherlands Antilles or Curacao, or some other small island somewhere. Which one works best is a lot down to personal preference:

We do also need to make sure our lawyer doesn’t give the game away doing something daft like this:

Mistakes can be fixed, of course, and a few days later the same article looked like this:

But on the internet nothing is gone forever (with thanks to the wonderful Wayback Machine) so it wasn’t hard to tie the Mauritius entity to Wirecard.

Why should we bother with the hassle of unscrupulous sellers, shady lawyers and offshore entities? Because we still need to cover for the fact that our company doesn’t really make money. It’s profit is fake, remember. And it’s starting to show on the balance sheet because we’re not collecting in cash. But now, suddenly, we can say we are.

We can say the money is coming in fine, every penny and on time. Analysts should like that. The cash came in - and then we spent it. Not because we had to. Because we wanted to. Because we see so many great opportunities to make even more for our shareholders, by investing behind new products that will expand our potential future sales up and to the right. Analysts will love putting that into excel.

Now, as funny as it would be to buy an “AI developer” in Bangalore that’s really just a curb side phone repair shop, we’re not going to. It’s too tempting for someone cynical to get on a plane and check what’s really there. And there’s a much better way for us to go.

We’re after that certain je ne c’est quoi of proprietary technology. The “you know it when you see it” of accounting - intangibles. That’s why Lemonware is such a gift to our fraud, a never ending opportunity to fake investment. The fruit of all that made up labour could be floating in a cloud somewhere, forever out of reach of auditors and law enforcement. They can look but not touch. After all, how long is a piece of code?

What makes this work is that cashflow is not all born equal, in the eyes of shareholders anyway. Normally we wouldn’t get credit for spending money because it means there’s less to go round for investors. You don’t need to be a sophisticated analyst to use cash numbers instead of the depreciation in the profit and loss, and that would be pretty bloody in our business. But not if the money is haemorrhaging into growth. This is different. This is our bright future. It’s deferred profit. It’s compounding. You surely aren’t going to count that as an expense, are you?

Only what we say is maintenance capex goes into the sum function for terminal value, because we can we claim that’s all we still need after we stop growing. The rest can be put in a separate line and safely ignored. Our made up spending will be buried six rows under all that growth capex, adjusted free cash flow will be in the black and everyone is happy again.

I’ve seen a few listed companies stretching the limits of credulity between actual and maintenance capex. But none ever topped a marketing firm I was short about 15 years ago. Beginning in 2005, a little before it listed in London (yes, on AIM) the company went on an investment binge. Capitalised spending rose from only a few percent of sales to over half, and stayed around 20% for the next 5 years.

There are a few ways an investor can get some insight into that number, without even looking to see what it’s spent on. One is to compare it with similar companies. If you looked at the kind of business this management wanted you to believe they were competing with – mobile ad networks like, say, Millennial Media - you were in for a surprise. Millenial spent about 3% of sales on capex.

But you didn’t even need to get that specific. A fifth of sales going into capex is a lot for almost any established business. So another way of making sense of it is to ask what kind of operation needs that level of investment? Before you go and search for the answer, have a guess at what the most capital intensive companies are (I went for transport infrastructure, things like toll roads and airports). If you did screen for companies that had capex over 20% of sales back then you ended up with a pretty short list (leaving out start-ups with little or no revenue, which were mostly biotechs and junior miners). The list was more utilities and telcos than transport as it turned out, but there were a few airports (and some airlines as well). Shockingly no advertising agencies made the cut.

The best clue that the investment was bogus, though, was what the company stated it was spending it on. Software, sure. But not code they developed themselves, this was programming bought off the shelf. When I asked management to break it down the best example they could give was Microsoft licenses!

We can do much better than that. We are can say we’re developing something along the lines of:

“data activation solutions that enable enterprises to activate petabyte and exabyte-scale data trapped in their internal systems, making it immediately available in the cloud to leverage the latest advancements in machine and AI-based cloud analytics”.

No I don’t have clue what that means. But thanks to this made up investment we can also now say that our business is not just profitable and growing fast, it’s free cash flow positive on an adjusted basis too. It still doesn’t make any actual money, of course. But that’s not what investors care about. If we keep pumping up the share price then they are right, and we’re alright.

Interesting to see that UK's market enforcement agency is as useless as U.S's SEC.